skin: the largest and most exposed human organSkin

The Body’s Largest, Most Exposed and Most Regulated Organ

Human skin is the largest organ of the body, representing approximately 15 to 20 percent of total body weight and covering close to two square metres in the average adult. It is not cosmetic. It is a metabolically active, sensory, immune, and regulatory organ that plays a central role in maintaining health and internal stability.

Skin is the body’s primary interface with the external environment. Unlike internal organs, which operate in relatively stable conditions, skin functions at the boundary between the body and constantly changing external variables including temperature, humidity, airflow, pressure, friction, microorganisms, light, and movement. Because of this role, the physical conditions at the skin surface directly influence systemic physiology.

Skin as an environmental regulation system

Skin continuously senses environmental inputs and converts them into physiological responses. Thermal sensors, pressure receptors, stretch receptors, and pain receptors embedded in the skin feed real-time data into the nervous system. This information drives adjustments in circulation, sweating, posture, behaviour, hydration, and energy expenditure.

Skin therefore functions as a regulatory system rather than a passive covering. When its interaction with the environment is altered through sustained coverage, compression, or ventilation restriction, regulatory efficiency is reduced and compensatory strain increases elsewhere in the body.

Structural and functional organisation of the skin

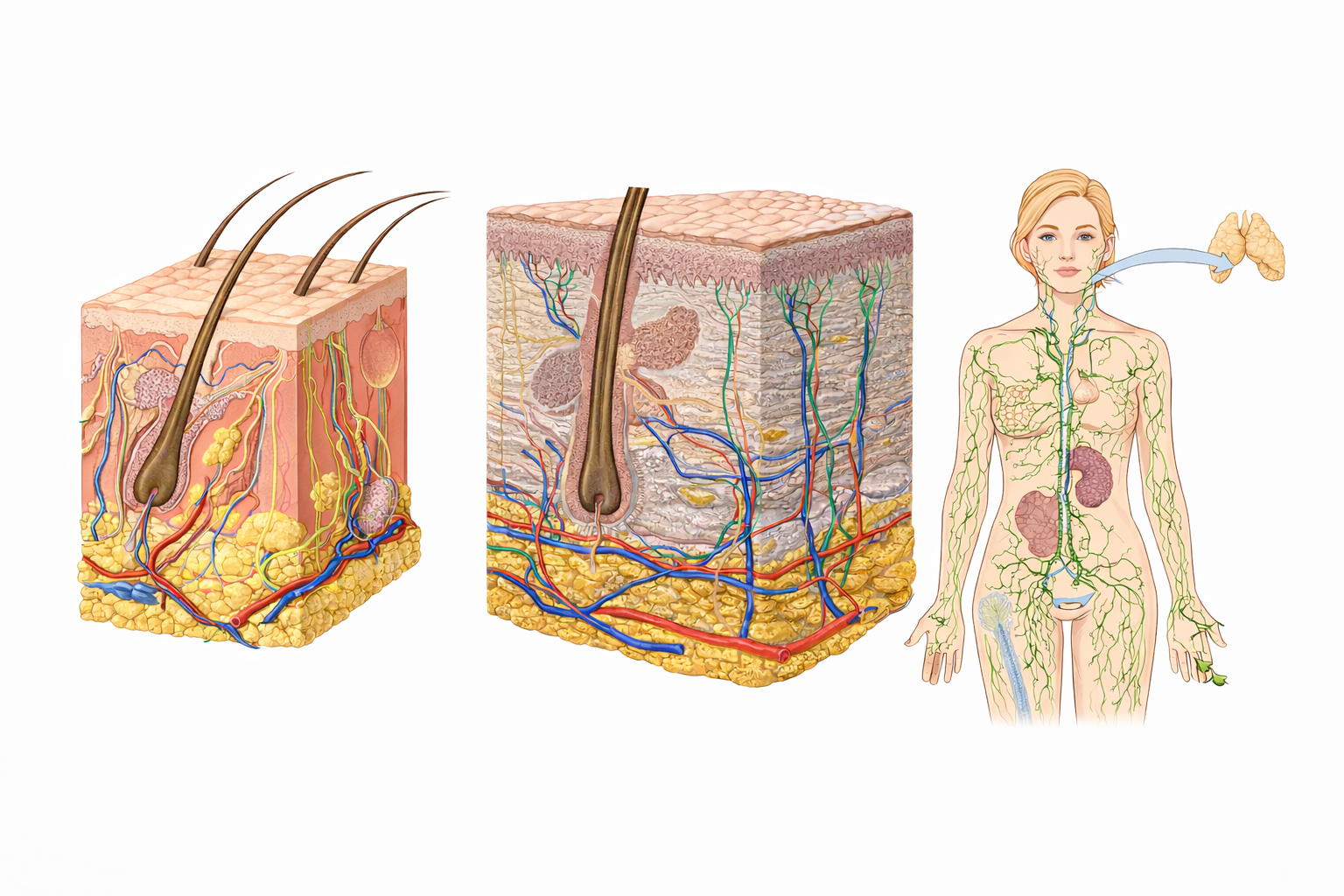

Skin consists of multiple layers working together as a single organ:

The epidermis provides barrier protection, microbial defence, and water retention

The dermis contains blood vessels, nerves, immune cells, sweat glands, and connective tissue

The skin surface hosts a complex microbiome that contributes to immune defence and barrier stability

These layers are integrated with the nervous, immune, circulatory, and lymphatic systems, making skin a key coordinator of whole-body function.

Core physiological functions of the skin

Barrier protection

Skin forms a physical, chemical, and biological barrier against injury, dehydration, toxins, and pathogens. Lipid layers, antimicrobial compounds, immune surveillance cells, and microbial competition all contribute to barrier integrity. When this barrier is disrupted through friction, moisture retention, or pressure, inflammation and sensitivity increase.

Thermoregulation and heat exchange

Skin is the primary organ responsible for regulating body temperature. Heat is dissipated through vasodilation and sweat evaporation, while heat is conserved through vasoconstriction. Evaporation is essential. Sweat that cannot evaporate does not cool the body. When airflow is restricted or moisture is trapped, thermal strain increases even in moderate conditions, placing additional load on cardiovascular and metabolic systems.

Immune defence and immune balance

Skin contains specialised immune cells that detect pathogens, coordinate inflammatory responses, and help establish immune tolerance to non-threatening environmental exposure. Chronic irritation or barrier disruption can shift the immune response toward persistent low-grade inflammation rather than balanced defence.

Sensory input and nervous system integration

Skin is densely innervated and provides continuous sensory feedback related to touch, pressure, vibration, temperature, and pain. This feedback supports posture, coordination, balance, thermal awareness, and behavioural adaptation. Reduced or dampened sensory input at the skin surface can impair intuitive regulation of comfort, heat, and movement.

Fluid regulation and tissue support

Skin works in close cooperation with microcirculation and the lymphatic system. It supports fluid exchange at the tissue level, assists immune transport, and contributes to waste clearance. Inflammation, compression, or reduced movement at the skin surface can interfere with these processes.

Metabolic and endocrine activity

Skin participates in vitamin D synthesis under ultraviolet exposure, contributes to local hormone signalling, and supports circadian rhythm regulation through light and temperature sensing. These functions link skin directly to bone health, immune function, sleep quality, and metabolic regulation.

Effects of sustained skin coverage and compression

Skin is biologically adapted to operate with airflow, temperature variation, and mechanical freedom. Prolonged occlusion and compression alter these conditions in predictable ways.

Common physiological effects include:

Reduced evaporation of sweat and impaired cooling

Increased local heat retention and humidity

Greater friction between skin and fabric

Repeated microtrauma at seams, elastic bands, and folds

Barrier disruption in high contact areas

Alteration of the skin microbiome in warm, enclosed zones

Increased inflammatory responses in susceptible tissues

These effects are mechanical and environmental in origin. They do not depend on hygiene, intent, or behaviour. They arise from altered heat transfer, moisture dynamics, and tissue mechanics.

Skin, movement, and mechanical adaptability

Skin is designed to stretch, recoil, and glide with movement. Movement supports circulation, sensory feedback, and tissue resilience. Prolonged immobility combined with tight or restrictive coverage reduces skin adaptability and increases local tissue stress.

Over time, this contributes to discomfort, stiffness, pressure sensitivity, and reduced tolerance to heat and friction. These changes are gradual and often normalised, but they reflect increased physiological load rather than optimal function.

Skin exposure and regulatory efficiency

Periodic exposure of skin to air and temperature variation restores natural regulatory feedback loops. This does not imply constant exposure, nor does it override the need for sun protection or context-appropriate clothing. It reflects the biological reality that skin function improves when ventilation, sensory input, and mechanical freedom are restored.

Potential benefits include:

More efficient thermoregulation

Reduced moisture retention

Lower friction related irritation

Improved sensory awareness and comfort

Reduced inflammatory burden at the skin level

Support for underlying connective and lymphatic tissues

These effects are cumulative rather than immediate, but they meaningfully reduce regulatory strain over time.

Key principle

Skin is a dynamic regulatory organ evolved for direct interaction with the environment. When its natural functions are supported rather than chronically constrained, the body operates with lower thermal stress, reduced inflammatory load, and improved adaptive capacity.

Fascia

The Body’s Continuous Connective and Communication Network

Fascia is a continuous, body-wide connective tissue system that surrounds, supports, separates, and integrates muscles, organs, nerves, blood vessels, and bones. It is not packing material. It is a living, responsive tissue network that plays a central role in movement, circulation, sensory awareness, and structural integrity.

Fascia connects every part of the body to every other part. There are no isolated muscles or organs. Mechanical forces, fluid movement, and sensory signals are transmitted through fascial pathways.

Fascia as a system, not a structure

Unlike discrete organs, fascia functions as a distributed system. It forms layers and planes that allow tissues to glide, transmit force, and adapt to movement and load. Because fascia is continuous, restriction or dysfunction in one area can influence distant regions.

Fascia operates at the intersection of the mechanical, circulatory, nervous, and immune systems. Changes at the surface of the body, including pressure, compression, or movement restriction, propagate inward through fascial connections.

Structural organisation of fascia

Fascia is commonly described in interconnected layers:

Superficial fascia located just beneath the skin

Deep fascia surrounding muscles, bones, and joints

Visceral fascia supporting and suspending internal organs

These layers are not separate systems. They are continuous and mechanically integrated.

Superficial fascia is particularly sensitive to surface conditions because it lies directly beneath the skin and contains blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, nerves, and connective tissue fibres.

Core physiological functions of fascia

Force transmission and load distribution

Fascia distributes mechanical forces generated by movement across the body. Rather than muscles acting in isolation, force is transmitted through fascial chains. This allows efficient movement and reduces stress concentration at individual joints or tissues.

When fascial glide is impaired, force transmission becomes less efficient, increasing strain on muscles and joints.

Tissue glide and movement efficiency

Healthy fascia allows tissues to slide smoothly over one another. This glide reduces friction during movement and supports fluid, coordinated motion. Fascial stiffness or dehydration reduces glide and increases mechanical resistance.

Structural support and posture

Fascia contributes to posture by maintaining tension and alignment throughout the body. It responds to habitual postures, loading patterns, and movement variability. Prolonged static positions encourage fascial shortening and stiffening over time.

Sensory signalling and body awareness

Fascia is richly innervated with sensory receptors. It plays a major role in proprioception and interoception, informing the nervous system about body position, tension, and internal state. Altered fascial tension can distort sensory feedback and contribute to discomfort or disorientation.

Circulatory and lymphatic integration

Blood vessels and lymphatic vessels travel through fascial planes. Fascia supports fluid transport by maintaining open pathways and responding to pressure changes created by movement and breathing. Fascial restriction can impair local circulation and lymphatic drainage.

Inflammatory and immune interaction

Fascia contains immune cells and responds to injury or irritation with inflammatory signalling. Chronic mechanical stress or compression can sustain low grade inflammation within fascial tissues.

Fascia is hydration dependent

Fascial tissue is viscoelastic and highly dependent on hydration. Adequate hydration allows fascial layers to remain supple and mobile. Dehydration increases tissue stiffness and reduces glide.

Movement is equally important. Fascia relies on regular loading and unloading to maintain elasticity. Lack of movement combined with surface compression accelerates stiffening.

Effects of sustained surface compression and restriction

Because superficial fascia lies directly beneath the skin, it is particularly affected by prolonged surface pressure, tight garments, rigid seams, and limited movement.

Common physiological consequences include:

Reduced tissue glide

Increased local stiffness

Altered force transmission

Localised fluid accumulation

Impaired lymphatic drainage

Distorted sensory feedback

Increased perception of tightness or restriction

These changes are gradual and often normalised, but they reflect increased mechanical and regulatory load on the body.

Fascia, movement variability, and adaptability

Fascia thrives on movement variability rather than repetitive or static loading. Diverse movement patterns promote tissue elasticity, circulation, and sensory recalibration.

Extended periods of immobility, especially when combined with surface restriction, reduce fascial adaptability and increase tissue stress. Over time, this contributes to discomfort, stiffness, reduced range of motion, and slower recovery.

Relationship between fascia, skin, and lymphatic flow

Skin, superficial fascia, and the lymphatic system function as an integrated surface regulation layer.

Movement, breathing, and tissue expansion create pressure gradients that drive lymphatic flow. When skin and superficial fascia are chronically compressed or restricted, these pressure dynamics are reduced, impairing fluid transport and waste clearance.

This is a mechanical reality rather than a pathological condition. The system functions less efficiently under constraint.

Fascia and physiological efficiency

When fascia is free to expand, recoil, and glide:

Movement becomes more efficient

Mechanical load is distributed rather than concentrated

Circulation and lymphatic flow are supported

Sensory feedback remains accurate

Tissue recovery improves

When fascia is chronically restricted, the body compensates by increasing muscular effort and neural tension, raising overall physiological cost.

Key principle

Fascia is a living, adaptive network that depends on movement, hydration, and mechanical freedom. Chronic surface restriction and immobility reduce fascial efficiency and increase regulatory strain.

Supporting fascial health reduces mechanical friction, improves circulation, and enhances the body’s capacity to adapt to stress and movement.

Lymphatic System

The Body’s Silent Circulation and Immune Transport Network

The lymphatic system is a body wide transport and regulatory network responsible for fluid balance, immune surveillance, waste removal, and inflammation control. It operates alongside the blood circulation but follows entirely different mechanics. Unlike the cardiovascular system, the lymphatic system has no central pump. Its efficiency depends on movement, breathing, tissue expansion, and mechanical freedom.

Because of this, surface conditions at the skin and fascia level directly influence lymphatic function.

The role of the lymphatic system

The lymphatic system performs four essential physiological functions:

Fluid balance

Every day, fluid leaks from blood capillaries into surrounding tissues. The lymphatic system collects this excess fluid and returns it to the bloodstream. Without this process, tissues would rapidly swell and circulation would fail.

Immune transport and surveillance

Lymphatic vessels transport immune cells, antigens, and signalling molecules. Lymph nodes act as monitoring stations where immune responses are coordinated. This allows the body to respond to infection, injury, and inflammation efficiently.

Waste and byproduct clearance

The lymphatic system removes cellular waste products, metabolic byproducts, and debris that cannot be returned directly through veins. This clearance supports tissue recovery and reduces inflammatory load.

Inflammation regulation

By transporting inflammatory mediators and immune cells, the lymphatic system plays a central role in initiating, sustaining, and resolving inflammation. Efficient lymphatic flow supports timely resolution rather than prolonged inflammatory states.

Structure of the lymphatic network

The lymphatic system consists of:

Lymphatic capillaries that collect fluid from tissues

Larger lymphatic vessels that transport lymph

Lymph nodes that filter and analyse lymph

Ducts that return lymph to the venous circulation

A large proportion of lymphatic vessels run through superficial and deep fascial planes, particularly just beneath the skin. This anatomical reality makes lymphatic flow sensitive to surface compression and tissue stiffness.

How lymph moves without a pump

Lymphatic flow relies on several mechanisms working together:

Muscle contraction during movement

Breathing, especially diaphragm movement

Pressure changes created by tissue expansion and recoil

Valves within lymphatic vessels that prevent backflow

Any factor that reduces movement, breathing depth, or tissue expansion reduces lymphatic transport efficiency.

Skin, fascia, and lymphatic interaction

The lymphatic system does not operate in isolation. It is mechanically integrated with skin and fascia.

Superficial lymphatic vessels lie directly beneath the skin within the superficial fascia. When this layer is:

Chronically compressed

Inflamed

Dehydrated

Restricted by limited movement

Lymph flow slows.

This does not necessarily cause immediate disease. Instead, it increases physiological load and reduces the system’s margin of efficiency.

Effects of reduced lymphatic flow

When lymphatic transport is impaired or slowed, common outcomes include:

Localised swelling or puffiness

Sensations of heaviness or fatigue

Slower tissue recovery

Prolonged inflammation

Increased sensitivity or discomfort

Reduced immune responsiveness at the tissue level

These effects are often subtle and diffuse, making them easy to dismiss or misattribute.

Movement and lymphatic efficiency

Movement is the primary driver of lymphatic circulation. Walking, stretching, changing posture, and deep breathing all support lymph flow.

Prolonged immobility, especially when combined with surface compression or restrictive clothing, reduces lymphatic pumping and encourages fluid stagnation.

This is why swelling and stiffness are commonly reported after long periods of sitting or inactivity.

Breathing and lymphatic transport

The diaphragm plays a critical role in lymphatic movement. Each deep breath creates pressure gradients that pull lymph upward through the thoracic duct and into the bloodstream.

Shallow breathing reduces this effect. Restricted posture, tight garments around the abdomen or chest, and prolonged sitting can all reduce diaphragmatic movement and lymphatic efficiency.

Lymphatic function and tissue health

Efficient lymphatic flow supports:

Faster recovery from physical stress

Resolution of inflammation

Immune balance rather than chronic activation

Healthy tissue hydration

Reduced swelling and discomfort

When lymphatic flow is reduced, tissues retain fluid and inflammatory byproducts for longer, increasing regulatory strain.

Surface conditions and lymphatic load

Because lymphatic vessels depend on mechanical forces rather than a pump, surface conditions matter.

Chronic compression, restricted movement, reduced ventilation, and prolonged immobility all increase lymphatic workload. The system can compensate, but compensation comes at a cost in efficiency and resilience.

Key principle

The lymphatic system is a silent but essential circulation that depends on movement, breathing, and tissue freedom. When surface tissues are allowed to expand, glide, and move naturally, lymphatic flow is supported and inflammatory load is reduced.

Supporting lymphatic function is not a specialised intervention. It is a direct consequence of how the body is allowed to move and interact with its environment.

Practical conclusion on clothing and physiology

From a physiological perspective, clothing is a functional tool rather than a biological requirement. The skin, fascia, and lymphatic system are designed to operate with airflow, movement, temperature variation, and mechanical freedom. Where conditions allow, reducing unnecessary coverage, compression, and occlusion supports more efficient thermoregulation, tissue glide, fluid movement, and sensory feedback. For this reason, minimal or no clothing, when safe, lawful, and contextually appropriate, represents the lowest-interference state for surface regulation systems. Clothing remains valuable where protection is required, but excess or continuous coverage should be understood as a trade-off rather than a default for health.

Want to explore related NRE Health content?

You can also listen to NRE-HEALTH Radio, an independent health information stream.

Click here to listen.